Dieckhoner, Gene

Riding the Artistic Currents

Making a living as an artist is not an easy path. But it can be a very interesting one. Just ask Gene Dieckhoner.

His journey began in Shaker Heights, Ohio, a suburb of Cleveland, in 1941. He was the youngest of three boys and the son of a man who could have been the inspiration for the TV show, “Father Knows Best.” His father, who was employed by the rapid transit system, was a proponent of traditional values, and if his parents argued it was always out of earshot of the children. They didn’t have a lot of money, but as Gene remembers, “If we were poor we didn’t know it, and we did just fine with what we had.”

His childhood years coincided with the World War II years, when everyone did with less. With a certain nostalgia Gene remembers “Meatless Tuesdays,” ration booklets, and, on VE Day, marching up and down the street banging his mother’s wash pan with a spoon in celebration of the end of the War.

As far back as he can remember, picking up a pencil and drawing on paper was as natural as getting dressed. He was a copyist in those days, re-drawing characters in his favorite comic books – from Yosemite Sam to Donald Duck – as well as magazine covers. One of his favorite drawings, which he still has, was a pen-and-ink stippled portrait of Humphrey Bogart.

From the time he first started thinking about what he was going to do when he grew up, Gene knew it would have something to do with Art. And because he was such a fan of the old magazine illustrators, he set his sights on becoming an advertising illustrator.

After graduating from college with a major in advertising and a minor in watercolor painting, and then serving three years in the Air Force, Gene went to work for an advertising agency in Los Angeles. It was the business he’d set his sights on; but once he arrived and found himself producing mechanical paste-ups and graphs for flip-charts, he began to yearn for more creative outlets. This led him on weekends to outdoor art festivals. At first he frequented them for fun, as a spectator. That changed when he found himself looking at paintings and thinking, “I can do better than that.” Already tiring with advertising, “I thought to myself I didn’t want to wait until I was sixty and wonder why I didn’t try this earlier.”

At the beginning he did not specialize. Anything and everything was his subject matter. It was when he realized that there were not a lot of really good wildlife painters that he specialized, and it became a good career move.

What distinguished his wildlife paintings was a genuine ability to capture the personality of his subjects. None of his animals were generic. He was able to render them in a way that left the viewer feeling they were preserved in a precise moment in time. His mission statement for his art was “To bring an awareness of the world around us; to inspire appreciation of the vastness and diversity of this great land; to revel in the joy of life reflected in the serious and comic exploits of those creatures who share our planet…”

If you would just pause for a few seconds longer the next time you see a cardinal resting on a branch, or a coyote crossing the road, or a hawk riding the air currents, he would feel his artwork had made a difference.

The major challenge he faced was how to come by fresh wildlife imagery. He was living in LA where the “wildlife” walked on two legs not four, and it simply wouldn’t do to work off the cover of last week’s Outdoor Life magazine. So he started stalking wildlife with a camera in zoos. And he reached out to people who stopped by his booth at art shows, which turned out to be a surprisingly rich source of imagery. It was amazing how many wealthy, eccentric people there were in the Los Angeles area who collected exotic animals as pets. Some were adopted from small circuses that closed down, some were the subjects of tragic mistreatment by abusive owners written about in the newspaper. These people had large properties and larger hearts. And they would build cages for bears, lions, tigers, ocelots, eagles, hawks to live the rest or their lives in peace.

This was how Gene met the actress Tippi Hedren, who had a particular soft spot for abused animals. And Amanda Blake – Miss Kitty from the TV show “Gunsmoke” – who invited him to come to her backyard zoo in Phoenix where she had lions, cheetahs and foxes. He would visit. He would take pictures that he used as references for his paintings. And, as word got around, the travel-photograph-and-paint opportunities expanded.

Many of the people whose animals he used as models would buy the original paintings, so the arrangement also created a built-in collector base. But you give up security when you decide to drift on the artistic currents of outdoor art shows. There were up and down years, when he depended on the income of his wife Diana to pay the bills, and there were intervals where he took a “straight job.” The most enjoyable was a five-year stint with Fox Animation where he did background paintings for video games. He would get the script for a story – say a space station on an asteroid – and it was up to him to put the words into pictures, and to even construct the props. He also supplemented his fine art income with two series of collector plates for Bradford Exchange. The painted series featured endangered species from around the world, while the sculpted series featured birds of prey in relief.

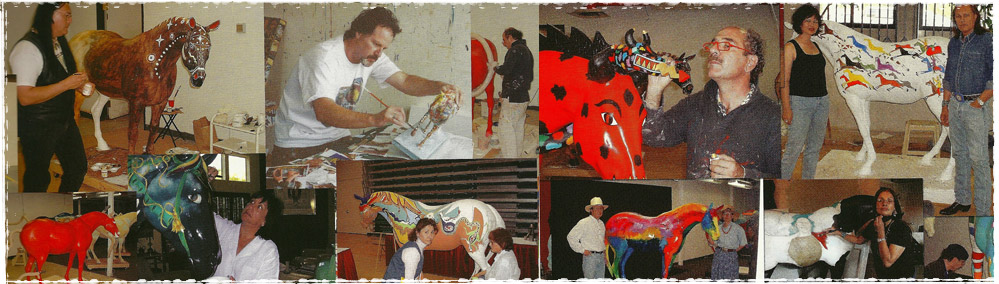

Then along came The Trail of Painted Ponies, which gave him the opportunity to combine two-dimension and three-dimension into something different. His first maquette Pony – “Take a Walk on the Wild Side” – depicted animals from the Sonoran desert emerging from the Pony’s body and sold immediately to a collector of original Painted Ponies. His second Pony – “Singing Cowboy Pony” – actually turned into a series of original Ponies playing different instruments that he sells himself at the various art shows he continues to do. His third Pony – “Dog and Pony Show” – has just been released as a figurine and is a playfully yet artistically rendered Pony cloaked with different animal breeds, each rendered in a way that captures the charm and personality of the individual dog in a way that only a painter who has ridden the artistic currents for his entire adult life could achieve.

Painted Pony figurines by Gene Dieckhoner:

- Dog and Pony Show

Additional Information

Where do you live?

For the past 23 years, Sedona, Arizona. It’s the only place I’ve lived where I’m always happy when I come home.

Where do you do your art?

My studio is a back bedroom in the house that has been remodeled into a natural studio. But this is not the kind of job where you punch in and clock out. Thinking is a big part of the work, and I do that everywhere. Driving, walking.

From where or who do you draw your inspiration?

I’m a big fan of the early 20th Century illustrators. Rockwell, Wyeth, Cornwall… the giants in the heyday of illustration. Before 1949, before photography took over, books, magazines and newspapers all relied on illustrators. Those guys are my heroes.

How would you describe your artistic style?

Realism. Not photo-realism, but what I call American-realism.

What is your favorite movie?

The one I’ve seen the most number of times is The Searchers, which I first saw when I was in high school. And it was all because of a single shot in the movie, and the fact that I was in love with Natalie Wood. The shot? She was a white girl who had been kidnapped by the Indians, and the first time we see her she’s in a teepee, the lighting is soft, and she looks gorgeous. I saw that movie five times in one week.

Who is your hero?

I know it sounds like a cliché, but my dad. For the way he lived his life. He dropped out of school in the 6th grade to help take care of his family. And he was an old-fashioned guy who believed in old-fashioned values and for whom family came first. Not that he wasn’t firm. Just like in the military, he held you accountable for your word, and if you said you were going to do something you’d better do it, because no excuses would be tolerated.

Favorite words of advice?

Easy. Treat others the way you want them to treat you.